CONTINUED

“The Devil’s Tongue of Blue John Gap”

by Derrick Belanger

Emory never fit in with the locals, excelling in his schooling and dreading the summer months of reaping the wheat, rye, and lentils. He loved learning, proudly answering abstract math equations in school; impressing his teachers while his classmates studied him with an odd glare, their lips slackened, slightly agape. It was not unusual for Emory to catch one of the boys in his class drooling.

While Emory did not fit in with the others, he was not an outsider. Unlike the other children, Emory studied up as best he could on the latest styles and fashions. He kept his hair slicked back and would save his money, every bill and coin he scraped together for an annual sojourn to London, to Herrod’s, to buy one suit of the latest fashion, a necktie, and a mid-level bottle of cologne. Emory’s fashion sense coupled with his strong jaw and dark brows around his emerald eyes caught the attention of many of the girls his age. Though, Emory had no interest in them. The residents of Blue John were noted for their slightly longer arms and mild bend to their backs. Emory covered the peculiarities up as best he could, focusing on an athleticism to straighten his spine, holding a rigid posture and using a muscular frame to hide his lengthy appendages. While the boys his age did not understand why Emory didn’t enjoy toiling in the fields, they respected his prowess, envied his skill with a football; and he always won the hay toss at the annual Blue John Faire. Emory hated the games, though. He hated the sports. He hated those who found joy in such menial tasks. Emory hated his father.

Ronald Gadfeld was, in many ways, the master of the hills of Blue John. Like the other farmers in the area, he had started out as a sharecropper to Lord Cecily. When the Lord and his son were killed in the Great War, the title trickled down through several other men and lads whose fate was found in the trenches. Eventually, the title settled on a far distant cousin who was desperate for money. Mr. Gadfeld was a shrewd man. He was able to secure a bank loan in London through dishonesty, and with the money, bought up his own farm and six additional ones surrounding his property. He then continued renting out the other five farms and used the money to pay back the loans. The only other man in Blue John with the foresight to make such a deal was Warren Hutchcroft who bought his own farm and three others nearby, though his land was more of a patchwork and less desirable to sharecroppers.

The Gadfelds and the Hutchcrofts had always had a feud though no one in the area remembered how it started – it just had – and so it continued on to the present day. Gadfeld was often heard grumbling about how Hutchcroft ran his farm, and Hutchcroft told his children they could marry anyone they wanted not named Gadfeld. Emory saw the feud as out of date and stupid. His brother and the Hutchcroft children agreed, but they kept up appearances so as to avoid the wrath of their fathers. They just maintained a cool distance from each other in school and in town.

Emory’s father never understood him. He found his son to be rather queer and couldn’t understand how he could want to run away from his heritage. Emory’s shunning of Blue John drove a bitter wedge between himself and his father. Emory never understood why his old man focused so much on Emory’s older brother William. William was the one who would inherit the farm, and he truly wanted to inherit the farm. It was William who father schooled, William who had the honor of learning the strange language of the ancient tomes which Father consulted, and it was William who he sent away to study in America, at Miskatonic University, in the coastal town of Arkham.

While William was studying in America, Emory made it a point to rise out of the hills on his own accord. He received a scholarship to be on the Oxford rowing team, made blue, and was able to attend the school without asking his father for any money. Emory never knew how much his father admired his fortitude, his ability to make his own path in the world; nor did his father ever get the opportunity to tell him, for it was the fate of his father and the strange etchings made in his hay fields which brought Mr. Emory Gadfeld to 7 Praed Street, to the home of the great detective known as Mr. Solar Pons. It was there where he and Mr. Parker first laid eyes on Mr. Emory Gadfeld and where one of the weirdest cases in the career of Solar Pons began.

*****

“I received an unusual phone call this afternoon,” Pons told me while stuffing his briar pipe with that horrid blend of cheap tobacco he so loved.

“Unusual?” I asked, putting down my medical bag and removing my overcoat. I had just returned from the residence of a patient whose daughter was suffering from brain fever. The fever had thankfully broken, and it appeared that there would be no permanent damage to the young girl.

Pons struck a match, lit his briar pipe, and took a few puffs. The putrid smell began to fill the room as fingers of smoke spread their reach through the air and pooled at the ceiling. Pons let out a thick plume through his nostrils and then answered my question. “Unusual in that it is a country dweller, a farmer, if you will, who claims that his crops have been trampled and his livestock slaughtered.”

I poured myself some brandy and went to the window, opening it a crack so as not to be strangled by the air fouled by my friend. I took a seat at our dining table, across from the detective, and stared into his steel grey eyes. The skin around them crinkled as Pons smiled, happy to have my company. “I’m assuming your telephone call was a short one. It sounds like a case for the local constabulary, not for a London detective.”

Pons’s smile broadened, emphasizing his hawkish facial features. “It was a short call, Parker. But not because I dismissed the man. I invited him here.”

“Here?” I leaned back giving Pons an inquisitive stare. “Whatever for? It should be quite a journey to come here only to have his case rejected.”

“Indeed, it would be; however, the young man is visiting London on business, and there are some… shall I say, peculiarities about the case which have piqued my interest.”

“I’m intrigued,” I admitted. “What makes this case stand out to you?”

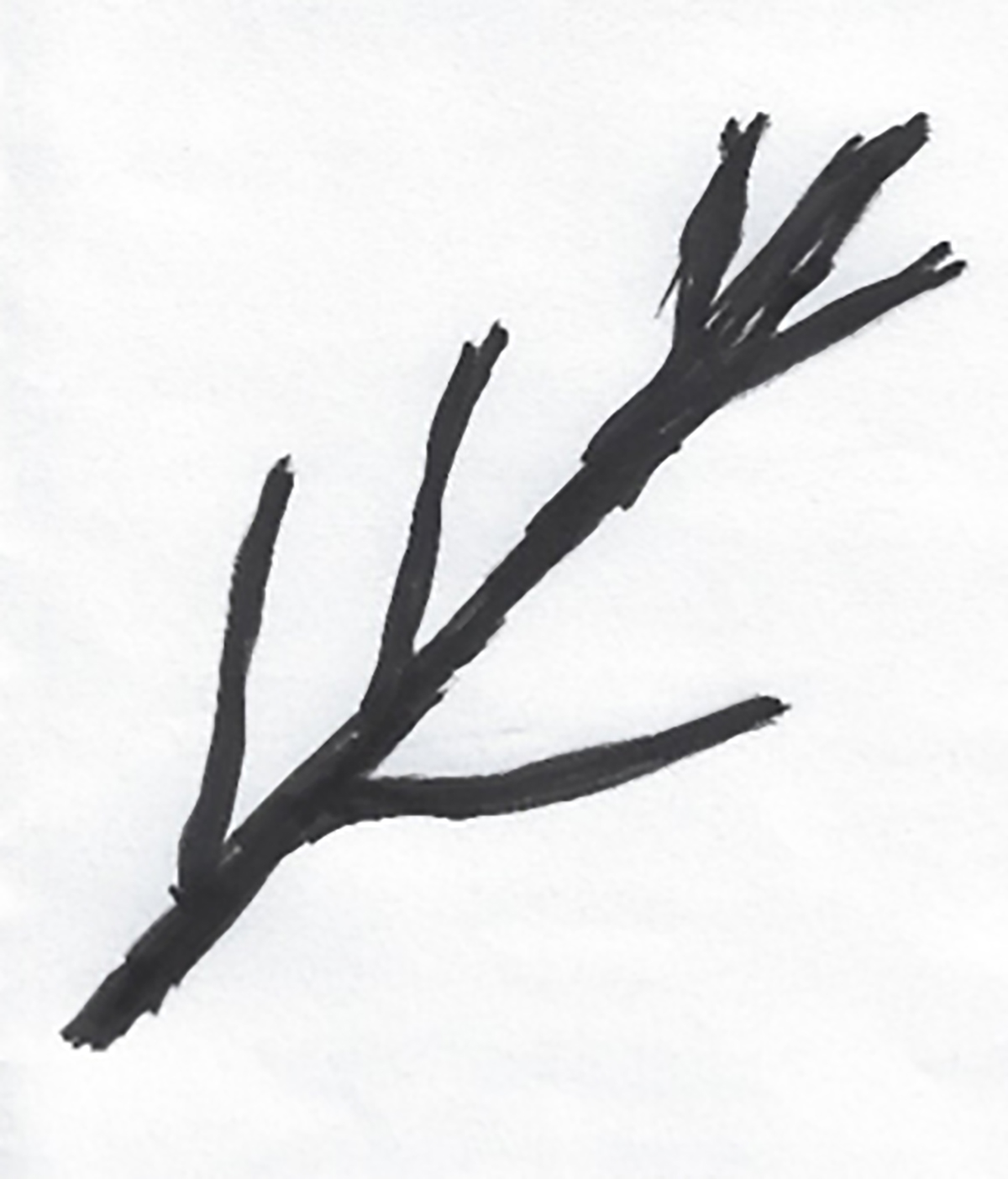

“The way in which the crops were trampled was with intent. The wheat was crushed in the pattern of a long thin line with five branches stemming from it. It is most likely nothing; however, there are a few questions I’d like to ask before dismissing his case outright.”

The pattern sounded random to me, but I knew better than to raise the issue with my friend. I could end up with a lengthy lecture on the meanings of druidic rune symbols. I simply nodded slowly, and took a sip from my brandy. “When will he arrive?”

In answer to my question, I heard a knocking downstairs and knew that the client was at the door.

Mrs. Johnson, our landlady, showed the man up to our rooms. He was an averaged size fellow but he seemed taller due to his rigid posture which gave me the impression he must be a military man. His eyebrows were dark and bushy and hair swept back with Pomade. His nose was flat and close to his face and eyes wide, emphasizing their sparkling emerald color. He introduced himself as Mr. Emory Gadfeld, and when he shook my hand, I noted that his arms seemed a bit long for his body, his grip iron. It was almost like he was a sharply dressed circus strong man. He wore the latest fashion, a blue pin stripe suit and red silk tie. There was something comical about the man’s appearance, as if he made a grand effort to dress to impress, most likely due to his farming roots. I stifled an awkward laugh thinking this man’s outfit was his effort to fit into London high society.

Pons shook Gadfeld’s hand and introduced both of us to the client. He then invited Mr. Gadfeld to join us in our recliners. I poured the man a drink and cut him a cigar. Soon we were all sitting, drinking, and smoking. The atmosphere was relaxed, and Gadfeld felt comfortable explaining the purpose of his visit.

“I thank you for allowing me to visit with you, Mr. Pons. You were the fifth detective I called. Three hung up the phone on me, and the fourth required a retainer fee so large to accept my case that I felt like he saw in me a country bumpkin easy to grift.”

“I can assure you, Mr. Gadfeld, that I shall hear your case, and if I accept it, shall work for a fair price. I cannot guarantee that I shall accept it.”

“That is all I ask, Mr. Pons.”

“Very good. Now tell me, Mr. Gadfeld, how a stick fighter such as yourself, an Oxford man with ties to America, a blue coxswain and oarsman – quite an achievement, mind you -came from country farming roots.”

Gadfeld looked astonished for a moment then he bristled, his cheeks flushing. “See here, Mr. Pons, I told you none of those things. Have you kept tabs on me? Has someone put you up to this?” There was malice in his voice as he asked the last question.

Pons gave out one of his odd silent chuckles at the outburst.

“Mr. Gadfeld, I assure you,” Pons grinned, “that I have spoken to no one outside of Mr. Parker here about your case.”

“But… I don’t see how you could know so much about me!”

“Well then,” said Pons with a quick clap of his hands, “allow me to explain.” Pons leaned back in his seat and pointed at the young man’s cuff links. “Those cuff links I have seen but once, in a catalogue for the company Macy’s in New York. Since you could get fine cuff links here in London without the great expense of shipping them overseas, it is clear to me that you either got them yourself or got them from someone who is in America or visiting America. Since you spend your time between Oxford and your home in Blue John, it is more likely that you received the cufflinks as a gift from someone you know across the pond, as the saying goes.”

“Humph,” Gadfeld said, thinking over Pons’s explanation. “You knew I was an Oxford man from my oarsman and coxswain pins,” Gadfeld said as he fiddled with them for a moment. “That much I can puzzle out myself. But how did you know about my stick fighting?”

“I noted the small indentations around your temple. They are different from those of a pugilist and would be received either by a stick fighter or one who fights with the nunchaku of the orient. Oriental fighting is still rather rare in the Empire, and so that can easily be ruled out. Then there is the fifth loop of your tie, a noted style from the members of Oxford’s ‘unofficial’ stick fighting club.”

“Well… I… well…” stammered Gadfeld. Then, he whispered as if we were out in a public square. “But the club is a deep secret. Practically no one besides me and my mates know about it. It is hush-hush.”

“One of my retired instructors is a stick fighter. There is much I learned from him which is, as you say, hush-hush,” Pons concluded. He straightened up in his seat and shifted to make himself comfortable. “Now, Mr. Gadfeld, my time is valuable. Pray tell me more about this assault to your property. Do not leave out any details.”

“Very well,” Gadfeld began. “You’ve impressed me Mr. Pons, and so I do hope you shall take my case even though you would have to travel to a Godforsaken part of the Empire, a squalid land of nothing but crops and simpleminded people.”

Pons’s brows furrowed. “I have no interest in your opinion of your country home, just in your case. Now, please get to the point.”

Gadfeld gave two quick coughs to clear his throat and then began. “It started early this month, soon after I returned to Oxford for my senior year. I received word that my father had died in a riding accident. His mare had stumbled, and father fell to the ground, his head striking a boulder. He passed instantly, leaving his estate behind for me and my brother.

“I secured leave for the semester and returned home.”

“You secured leave for the full semester?” questioned Pons.

“Yes, for my brother was unable to be notified. He still is unaware of my father’s passing.”

“But surely,” Pons interrupted, “a letter can make it to America in a week’s time.”

“It can,” Gadfeld explained, “but my brother is not in America.”

“Isn’t he at Miskatonic?” Pons asked.

“He is and he isn’t.” Gadfeld saw the baffling look exchanged between Pons and me, and so he hurriedly said, “What I mean is that he is enrolled at Miskatonic University but is away conducting research, some project studying the deepest point in the Pacific Ocean.”

Pons’s eyes widened at this explanation. “What, pray tell, is your brother studying?”

“Languages,” Gadfeld grumbled. “I know. I never understood it either. It’s a bit of a tradition for the first born in my family going back several generations. They always go away and study at Miskatonic. They always study languages. It has to do with the ancient tomes kept in father’s study. They supposedly help with the harvest. Bunch of superstition and gobbledygook if you ask me, but our farm has been successful, and so they continue on with the tradition.

“William is studying the writing of some ancient underwater city there. Heard Father mention it once, ‘Rill-yah’ I believe the civilization was called. Once he completes his study, his team will have their research published. Seems like such a waste for William. My brother is quite the scholar. He published a treatise on the Tcho-tcho people of the Anderman Isles last year and now this study of the Rill-yah language. He should go on to get his doctorate, but he’ll end up returning to the farm. Same as Father.”

I thought Pons would shoo away Gadfeld’s aside about his brother, but Pons was most interested. He even seemed bothered by the work of William Gadfeld. I noted Pons perspired slightly, and his eyes widened as he heard of William’s research. “Could you tell me the names of the texts in your father’s study?” Pons asked. Though Gadfeld wouldn’t be able to detect it, I noted a slight tremor in Pons’s voice. Something about Gadfeld’s family was making Pons nervous. His eyes subtly stayed widened while our visitor listed off the names of some of the books in his father’s study.

“Let’s see… they’re a queer lot, the closest one to English is The Necronomicon. There’s something Eibon, and then there’s one I’m guessing is French called Cultes des Goules, odd name, that one. Let me think, what else, De Vermis Mysteriis, maybe that’s another French one, maybe German. Languages were never my forte. That’s all I can recall off the top of my head… oh wait, Father had also recently acquired a bound set of papers called The Eltdown Shards. He was very proud of that one. Just got that this summer, shortly before he passed. There’re others as well. Stacks of them. Those are the ones that come to mind.”

As Gadfeld listed the books, Pons became more withdrawn. I could see his mind traveling deeper and deeper in thought. When Gadfeld stopped, Pons paused for a moment, and I noted him fiddling with his necktie, but the movements of his hands seemed to be making certain motions with intent. He looked up to Gadfeld after he rested his hands on his lap. His face turned down ever so slightly. “Those books are quite ancient and rare, Mr. Gadfeld, I understand why your brother studied at Miskatonic, for the only experts on those tomes are among that university’s faculty. Now, getting back to your case…”

“Of course, Mr. Pons, let’s see, where was I? Oh yes, so I returned home after being informed of Father’s death. Mr. Alexander, our main farm hand, greeted me warmly and showed me around the property. He had done an excellent job keeping everything running fine in the absence of my father. Alexander runs a tight ship, as they say. He kept the other workers in line. No one slacked off after Father passed.

“Mrs. Alexander, his wife, was very happy to see me. My mother had died of tuberculosis when I was a young lad, and so she had practically raised me. Although my feelings towards Blue John are negative, I have fond feelings towards the Alexanders.

“We dined that evening in the main house. Mrs. Alexander prepared a feast of which I was not deserving. But that is the way of women, I suppose, showing their love through their cooking. Anyway, it was that night when I first heard of the strange mutilations on our farmland.”

“Mutilations?” I asked. Pons motioned with his hands for me to be quiet. He wanted Gadfeld to continue uninterrupted.

“Yes doctor, some of the livestock were slaughtered in a way the likes of which Mr. Alexander had never seen before.

“First happened on the Jeppesons’ farm. The Jeppesons are one of the families that rents lands from us. They have a hundred acres just outside the hills. They raise wheat but have some livestock as well. Goats, sheep, cows, mainly for milk.

“Five of their sheep were found about three weeks ago, hideously mutilated. Their bodies were shriveled, completely drained of blood. Their genitals had been cut off and the animals’ eyes and tongues removed.

“When Alexander described the sheep, I was shocked and disgusted. ‘How horrid!’ I exclaimed.

“‘Aye, it was,’ Alexander said, a grim expression on his face. I could see that the incident scared him. ‘No signs of animal tracks or footprints near the bodies neither. Never seen anything like it.’

“‘Hush now, Thomas,’ Mrs. Alexander scolded her husband for she believed that the talk was upsetting me. In all honesty, gentlemen, I found myself fascinated. Who or what could cause such horror? I asked Mr. Alexander if there was a theory as to what could have killed the animals in such a gruesome fashion.

“Alexander looked over his shoulder to make sure his wife was out of distance in the kitchen and wouldn’t scold him for carrying on. ‘No one knows for sure. To be honest, everyone’s spooked. Constable Corbyn has asked around. He thinks it’s a bear or maybe a panther. I thought maybe the Hutchcroft kids were having a bit of fun, but there’s nothing fun about this, and I don’t reckon there’s any way they could have done this work without leaving footprints.’”

Gadfeld explained that the Hutchcrofts were the other prosperous family in the farms of Blue John. The Gadfelds had a feud with them going back decades. Gadfeld explained that he and his brother William had actually gotten along with the Hutchcroft children. They all believed the feud to be ridiculous, but their parents did not. They were forbidden from being friends, and because of this, were never close in school. It was generally understood among them that the feud between the families would end with the passing of their parents.

“And you concur with Mr. Alexander that the Hutchcrofts had nothing to do with the slaughter of your sheep?” Pons asked, but his question came out as more of a statement.

“I did... until last week,” continued Gadfeld. “Shortly after my return to the farm, other animal mutilations occurred, all from families renting our farm land. The first was the Hendersons; two of their goats and one of their heifers were found with the same organs and blood removed as the Jeppesons’ sheep, only this time the heifer had a strange marking on its body, almost like a large burn from the side of its neck down to its tail. The Larkhams also lost some cattle as did the Masons. Poor Mr. McRory, an old timer who only still has a small parcel of land to himself, lost his beagle and half his flock. The beagle was like his only kin. He loved it dearly. For the man to wake in the morning and find it shriveled with half of its face removed was too much for him. His heart gave out. We took him to the hospital, but he had passed by the time he got there.

“That was the last of the mutilations thus far. I hope it remains that way; however, soon after McRory’s death was when that odd symbol was etched in our field. It was last Thursday when O’Brien, one of our farmhands came across the strange formation. The Irishman reported it to Alexander, but he thought something had just trampled a large portion of the wheat. It wasn’t until Alexander took the duster up that afternoon that we got a good look at it. We were able to take this photograph of the crop symbol.”

Gadfeld reached into his breast pocket and removed a photograph with an image that looked like this:

There was nothing remarkable in the design. In fact, to me, it looked rather random. Perhaps some burrowing animals had infected his land and these were their pathways. When Pons looked at it though, his astonishment was clear to both me and to Gadfeld.

“This means something to you,” Gadfeld said, excitement building in his voice.

“It does,” Pons responded coldly. “It is a very old symbol, known by some of the natives in the South Atlantic. It is a powerful sign Mr. Gadfeld, one of protection.”

Gadfeld looked baffled. “Protection? From what?”

“From the killer of your livestock. This is all very troubling, Mr. Gadfeld. I can’t say I’m glad that you brought me your case for you have put us on a very dangerous path; however, it is auspicious for you that you did.”

“I don’t understand,” Gadfeld replied.

“No, you don’t,” Pons responded sternly. “And until I have more information, I’m afraid that I must leave you in the dark. I must conduct research, Mr. Gadfeld. Give me a day or two, and then I shall call you and let you know when to expect me.”

“You will come to Blue John?” he asked.

“I shall give this case my full attention. Now, one last question. You had said you had a suspicion about the Hutchcrofts.”

“I had almost forgotten, Mr. Pons. Yes, it may be nothing, probably is.”

“Let me be the judge of that,” Pons said bluntly.

“Very well. It was just before I left. Our farmhouse is two floors, Mr. Pons, and if one is having a discussion in the entryway the sound will travel up the stairs. I heard Mr. Alexander complaining to his wife about old man Hutchcroft. He had been enquiring about Father’s books. The old volumes – he wanted to buy them. Apparently, he had been asking Alexander about them several times, and pressing him on the matter. Alexander shooed the old man away, but I wondered how Hutchcroft even knew about Father’s ancient tomes. They rarely spoke, and I can’t imagine Father telling the man about his prized collection. I know it is probably nothing.”

Pons’s eyes drooped, and he looked to be in an almost meditative state, taking in all that Gadfeld had brought to him. “Perhaps, Mr. Gadfeld.” Pons said, his voice distant. “Perhaps.”

*****

Gadfeld was unnerved after his visit with Solar Pons. He found the detective’s concern for the situation disturbing. Pons’s nerves, and the way he fidgeted with his necktie, made him seem afraid of the case; and his claim that the symbol in the field was an ancient charm sounded like quackery. Still, Pons was the only detective interested in Gadfeld’s unusual case, and the man had an impeccable reputation, even called the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’. Plus, he was willing to travel to North-West Derbyshire, to Blue John. If he was a little eccentric but solved the case, why should that bother me? Gadfeld thought. Yet, it did. It made him think of his father and his peculiarities and those wretched books upon the shelves of his study.

Gadfeld shuddered. An image appeared in his mind of the stern and intense gaze from his father’s dark eyes. What would he think of this situation? Would he trust Pons? Then Gadfeld’s mind shifted, and he asked himself, Why was Hutchcroft interested in Father’s books? This thought made Gadfeld’s mind drift to the memory of his father’s funeral.

The funeral had been held on the Saturday after Ronald Gadfeld’s death. The weather was dreary, with a chill mist keeping the atmosphere dank and the ground too muddy to work. The church had been full with the locals and Emory Gadfeld wondered if the weather was the contributing factor, or if the community feared it was a funeral for them as well. With Ronald gone, who would be the overseer of the farms of Blue John? they questioned. With both Gadfeld’s sons as university men, would they sell off the land? What would become of the renters? Would the whole economy of Blue John collapse?

Emory had scowled as he read the questions from the concerned faces of the parishioners. It was his father’s funeral, after all. Did they really need to be concerned about themselves? Could they let him mourn for one day and allow him to put aside his hatred for the community?

Outside of the Alexanders and the workers at the farm, the one person who seemed surprisingly remorseful was Warren Hutchcroft. The old man shed no tears for Ronald Gadfeld, but he did hold his hat over his heart, recited the prayers for the departed, the mourners, and the penitence. The old timer appeared truly saddened that Gadfeld senior had died.

“He and I didn’t see eye-to-eye,” he explained to Emory when he greeted him after the funeral, “but we always respected one another. He did much for Blue John. The town won’t be the same without him.”

Emory accepted the condolences but inside he was reeling. You two despised each other, he thought, his lips pursing, containing his rage. But another thought made his lips move to a slight smile. He wouldn’t be so polite, Emory couldn’t help but think to himself, if he knew about my relationship with his daughter.

Sarah Hutchcroft was the one puzzle piece which never fit in with Emory’s plan of escaping Blue John. The two of them had been secret friends as kids, finding each other running in the fields of wild flowers between tracts of farms. Sarah taught Emory how to rub a buttercup below his chin to see if he liked butter. She taught him hide and seek and leap frog and other rough and tumble games most would say weren’t suited for girls. It was that tomboy approach to life which seemed to be the opposite of Emory’s primness which attracted Emory to her and her to him. While Emory cursed his classmates in secondary school, and always scorned the girls of Blue John, he found himself drawn more to Sarah. They dated, almost courted. They were each other’s first kiss.

But Emory had to escape from Blue John. He figured once he was away, at Oxford, he’d find girls more suited to him, those that cared about academics or at least were fashionable. And Emory did find such girls. But the more Emory dated, the more he found himself missing Sarah. He was surprised to discover when he returned to Blue John that like him, Sarah had yet to marry. Emory had seen Sarah but once since he returned to Blue John, and it was at his father’s funeral. She said she was sorry for his loss and then was quickly shuffled out, for the line of mourners had to keep moving. As Emory’s train approached the station, he thought of how much he wanted to see Sarah again. Perhaps he’d go over that afternoon. But it was not to be. Emory would have to wait two days before he’d see Sarah again, and at that point, he’d be in the presence of Solar Pons.

*****

Pons had intended for us to be in Blue John no more than 48 hours after Mr. Gadfeld left Praed Street, but it wasn’t until a full 96 hours later when we arrived in the rural farming community. Pons had spent the time almost immediately after Gadfeld said his goodbyes pouring over books, calling scholars with questions, even sending one of his Irregulars on a task of retrieving papers from an elderly luddite who refused to have a phone or even automobile on his property. One of the books I recognized from a title Gadfeld mentioned, The Book of Eibon. Most of the others were studies, academic discourses on other books mentioned by Gadfeld or, what I imagined, to be books in a similar vein.

I had left Pons for much of the first two days of his work, completing my own patient visits, rescheduling others, and setting up a locum to treat my patients when I’d be away in Blue John.

It was after those two days when I left my bedroom and stepped into the sitting room with my suitcase packed, ready for our next adventure. Instead of seeing Pons dressed with bags in hand, I was blinded by foul, acrid air pouring out from inside. When my vision cleared from the smoke, I saw my friend hunched over a text written in symbols unlike any I’d ever seen before. He had a magnifying glass in his hand, and he was staring at odd circular shapes similar to suction marks I’d once seen on the side of a ship which had encountered a squid. To the naked eye, the marks all looked the same. There must have been some subtle shifts that Pons could only detect with the amplification allowed from his spy glass. He had a piece of paper and once he’d go over every five shapes or so, he’d pause and scrawl a word or two down.

“You’ll have to take a break, my friend, if we are to catch the 3:10 out of Victoria,” I explained to him.

Pons didn’t look up from his study of the symbols. “I’m afraid that will have to wait. We can’t leave yet, not until I’m fully prepared.”

“Fully prepared?” I inquired, my eyes scanning the books stacked by his desk. I lifted one titled, A Treatise on The Cultes des Goules and Additional Esoteric Writings of Francois-Honore Balfour. I read the title aloud and asked Pons how this was going to help him in his studies. “Why are you looking at all of these treatises and not the original texts?”

Pons finally looked up from his translation work, took a few additional puffs from his pipe, leaned back and explained, “There is much to be learned from studies, particularly when the original works are unavailable.”

“But the original works are available. They are in Gadfeld’s father’s study.”

“But they shouldn’t be,” Pons declared.

“Whatever do you mean?”

“I mean those books are noted to have anywhere from three copies to a dozen copies in existence; that’s all. As you can see, in all of London, I was able to acquire but two original texts, The Book of Eibon and then these papers I am in the midst of translating. I had to teach myself the language before I could begin the work of reading them.”

“The language looks difficult to read. The writing all looks the same.”

“The markings are quite similar to us; however,” Pons pointed out two seemingly identical shapes, “to the writers, the differences of these two circles are as clear as the difference between the letters A and J are to us.”

“What people used such a language? Is it Druidic?”

“No, my friend. It is much older than that. Much older than the human race.”

“Surely, you jest.”

“I do not,” Pons responded soberly. “The beings who wrote these fragments once ruled over our Earth, back in the days when dinosaurs roamed the land.” Pons put down his calabash, stood from his chair, faced me, looked me in the eye to show his seriousness. “You have to understand, Parker, that this will be a case like no other. There is danger not from the barrel of a gun but from Godlike forces that could tear you from this Earthly realm.”

I had not seen my friend so serious and, quite frankly, terrified before. It left me rattled and I looked away for a moment, my mind trying to comprehend what Pons was saying. “Did you say ‘Godlike’?”

“Yes, that’s what they’ve been referred to, both the Great Old Ones, and the Elder Gods. They are called that, for that is what they seem to us. It is no different than if an amoeba could comprehend a human. It, too, would undoubtedly see us as almighty creatures. But these beings are actually just that, beings, from other parts of time and space, even other dimensions. I’m afraid, that is what we are up against in this particular case.”

“But how can we face such creatures?”

“There are ways. That is the point of my research. I must make certain we are prepared to face these beings from beyond the stars, to make sure that what is draining the livestock on the Gadfeld farm does not do the same to us. That is why we cannot, must not, leave until I have an idea of what we face. It is a matter of life and death not just for us, but perhaps for all of England and even the world.”

An additional two days passed after my conversation with Pons before we arrived at the small train station in the town of Blue John. We spent the ride playing chess, though I should say playing wasn’t the proper term when Pons beat me severely in every game. I could see his mind was in a strategic place, already running through scenarios which could possibly play out. He was not jumping to conclusions about what we’d be up against, merely running through all possibilities in his mind so as not to waste any time on the case when we arrived. He rarely spoke to me on the trip beyond commenting on a play, though we did both feel the elevation as our train ascended up to the valleys of Blue John which were no less than 1,400 feet above sea level.

When we departed the train, Emory Gadfeld was waiting for us. He was speaking with a young lady of about his same age. She was slender with a pretty face and long neck. I noted that like Gadfeld, she also walked with a very straight poise. She wore a long, billowy yellow dress, the sleeves were cut in a way that helped to mask her unusually lengthy arms.

Gadfeld greeted us with a warm handshake. Pons and I took off our hats and bowed to the lady when we met her. “Mr. Pons and Dr. Parker, this is Miss Sarah Hutchcroft.” Miss Hutchcroft gave a curtsy to us and then excused herself for she had to stop by the butcher before the steaks were sold out for the day.

When she left us, Pons remarked, “I see that the feud between your families, Mr. Gadfeld, is definitely not held between you two.”

Gadfeld’s cheeks reddened and he looked down at his shoes for a moment, a grown man looking like the embarrassed schoolboy. “Is it that obvious?” he asked.

“There is nothing wrong with young love,” Pons said to the man, giving him a firm grip on his shoulder.

“I tried my best not to love her,” Gadfeld explained. There was remorse in his voice, and his eyes dampened. “Our families would never allow it, and yet...”

“And yet here you are, both smitten with each other,” Pons concluded.

“I find in my own experience,” I added in, “that forbidden love is most often the flame that burns the brightest. Whether her family approves or not, you are both deeply in love, that is most obvious. I’d say the sooner you make it known to all, the better.”

Gadfeld looked terrified at the idea. “You mean propose to her. Her father would never allow it.”

“Times have changed, Mr. Gadfeld. Even if her father says no, you both can say yes.,” Pons said, giving Gadfeld a gentle shake.

“And besides,” I said mirthfully. “We saw you from a distance and could see the spark between you two. I doubt there’s a man or woman in Blue John who doesn’t know how you two feel about each other.”

After we gathered our luggage and loaded them into the trunk of Gadfeld’s automobile, we were on our way to his farm. I did not expect to find Blue John surrounded by limestone hills. “The ground here is soft,” Gadfeld explained as we drove along. “The caves go below the farmland which is one reason that the soil is considered so rich. There’re natural aquifers below the ground which keeps the land damp and aerated.”

“What of that entryway in the cave above the town?” Pons inquired. There was a jagged cave entrance in the hill above the town that was loosely boarded up.

“That’s Blue John Gap, or at least it was.”

“Built by Romans?” Pons questioned.

“Yes, that’s right Mr. Pons. The Romans built it when they mined the violet stones. This vein is tapped. There are still some mining operations in the other hills, but the amount of purple stone pulled out is less and less each year. It won’t be long before Blue John is solely a farming community.”

Gadfeld paused for a minute, shook his head as if making up his mind, and then continued. “There is one thing I probably should mention to you about Blue John Gap,” Gadfeld said.

“Yes?”

“Well, a few years back, there was an incident where some livestock were killed by a wild animal in the area. It was nothing like the animals on my farm, more like a typical wildcat or bear attack, which is why I didn’t mention it before. It probably has nothing to do with-”

“Go on,” Pons interrupted bluntly.

Gadfeld let out a sigh and continued. “Anyway, there was this fellow, Dr. Hardcastle, a visitor who was staying with the Allertons. He had come here for the altitude, hoping it would help his suffering. He had a severe case of tuberculosis. The doctor had developed a theory that the caves of Blue John were an entryway to a much deeper underground world below the surface of England.”

“And was Dr. Hardcastle’s theory corroborated in anyway?” I asked from my perch in the back seat.

“Not exactly, Dr. Parker. Hardcastle claimed he heard a monster inside the entrance to Blue John Gap, so he never went too far in his explorations. On his last excursion, he claimed he encountered the beast which was a towering albino bear. He said that he shot and killed the monster.”

Pons tensed at this story. “And the bear’s body?” he asked.

“That’s the strangest part. A few men went into the cave where Hardcastle claimed he killed the beast. They saw no tracks and no blood on the cave wall where Hardcastle claimed he had shot the thing. Certainly, no body. A few doctors from Bart’s came and inspected Hardcastle. They claimed tubercular lesions and his poor health caused him to hallucinate the experience.

“Even with the lack of evidence, the town’s people were spooked. They climbed up the hill and sealed the cave entrance to keep the beast from escaping. It wasn’t until last year when the mining company opened the entrance slightly to do another survey. They went down into the mine a good fifty yards. They found no evidence of any bear or subterranean land, nor did they find any additional veins of the purple stone. So, the logical conclusion is that Hardcastle imagined the whole thing.”

“Ah, yes that does seem logical,” Pons said almost sarcastically. “And the animal killings ended after Dr. Hardcastle’s incident in the cave.”

“Yes, that’s correct, Mr. Pons. My thought is that if there really was a bear, either the animal was trapped when the locals boarded up the gap, or it just moved on to another food supply.”

“Does anyone still explore the cave?” Pons inquired.

“Oh, I’m sure the local schoolboys probably have a lark in there. The entryway isn’t well sealed anymore. Besides that, I don’t know of anyone else exploring the cave from this entrance. As I said, there are other ways to enter the mines,” Gadfeld concluded. We then turned off the road onto a lengthy gravel drive between fields of summer wheat. A hangar was off in the distance and a two-story cape loomed before us. We had arrived at the Gadfeld farm.

Mr. Alexander and two young farmhands greeted us when Gadfeld parked his jalopy in the driveway. The farmhands, clearly brothers as both shared the same freckled faces and azure eyes, by the names of Pete and Lester took our bags. Alexander was a solid man with a firm grip. He had a bushy mustache and flowing gray locks housed under a Stetson hat. The man looked a bit like the depiction of Doc Holliday in some of the American Westerns.

“Begging your pardon, Em, but could we have a word in private?” Alexander asked Gadfeld after we had exchanged the usual pleasantries by way of introduction.

The brothers offered to show us to our room while the men spoke, and we took them up on the offer. The sooner we were settled, the sooner Pons could begin his investigation.

Pete and Lester led us up the steps of the front porch and through the front door. The farmhouse was an older, well-kept building. I could tell that Mrs. Alexander ran a tight ship. Everything was in order on the tables and shelves, and I could imagine that there’d be hell to pay if someone inadvertently knocked an item out of place and didn’t take the time to reset it.

The room Pons and I were to share was located on the ground floor at the rear of the house, the window view somewhat obscured by the tall fields of wheat, though we still had a clear enough view of the craggy entrance to Blue John Gap.

We thanked the young men for dropping our luggage, and soon after, they left, heading back to work. The room was a good size guest room with two twin beds. There was a sink and a bucket of water for washing, and an access door to a trail off in the back which led to the privy. This was the country after all.

“Where shall we start?” I asked my friend who was pushing down on his bed’s mattress, checking its firmness.

“We shall not start, at least not together. I would like for you to walk the grounds. Talk to the workers. See if there is anything out of the ordinary or anyone here who causes trouble. I’d also like for you to get a good look at the corpses of the desiccated farm animals. See if you can detect any additional information on their cause of death.”

I nodded at Pons’s instructions. “And you?” I asked.

“For now, I shall spend my time in Gadfeld’s library. I’d like to see if he really possesses the ancient texts, and if he does, spend some time conducting research.”

Almost immediately after Pons explained his plan, Emory Gadfeld was at our door. He had a scowl on his face which he tried to swallow away in our presence.

“Is something wrong?” I asked.

“It’s just O'Brien. He’s been drinking on the job again. Alexander caught him napping out back when he was supposed to be watering the crops. I don’t know what to do with him. Alexander thinks it may be time to let him go. Since Father died, I guess he’s been getting worse. Still, he’s been with the family for years. But this is my problem gentlemen, not yours.” Then, Emory added, probably not realizing he was speaking aloud, “I just want to go back to Oxford and be done with it all.”

“Cheer up, Mr. Gadfeld,” Pons said warmly. “We are here now, and I believe I shall have your case solved in a matter of a few days. Much will depend on what I uncover in your father’s library.”

Gadfeld did not look reassured. I could tell he thought Pons would find nothing of value in dusty old texts that would help his current situation. But Emory nodded and said he’d show Pons to the library.

“Will you be joining us, doctor?” Gadfeld asked, expecting me to say yes.

“No, if it is all the same to you, I’d like to take a look at the carcasses of the drained animals, see if I can learn any information from them.” Gadfeld brightened at this, believing the medical route could lead to clues as to what killed the animals.

“I’ll have one of the boys take you out to see the remains.”

“Have other animals eaten away at the carcasses? I’m wondering what condition I should find them in.”

It’s very strange. No scavengers have eaten away at the bodies, not even bugs’ll go near them.” Gadfeld shook his head, puzzling this over. “No one’s ever seen anything like it.”

“Did you happen to preserve any of the bodies? Put them on ice, perhaps?” I inquired.

“Sorry, doctor. The thought never occurred to me. I hope the bodies haven’t rotted too much and you can glean some useful information from them.”

Lester, the freckle faced farmhand who had shown Pons and I to our room, took a break from sweeping the front porch to show me to the bodies. The lad drove us over in a rickety, mud splattered bulldog. The truck ride was bumpy and did not lend itself to conversation. Along the way I thought of O’Brien, the drunken farmhand. He’d been the one to discover the symbol carved into the fields. I’d want to make sure I spoke with him later. I wondered if the crushed crops and the drained animals were the cause of his increased drinking.

It wasn’t long before we reached the pit which acted as the grave for the mutilated carcasses. Surprisingly, even without refrigeration, the bodies of the animals were in a well-preserved state. There were no flies buzzing around them. It was as though even the bugs were afraid of these bodies. Lester explained that all the carcasses were moved to the gravel field behind McRory’s house. Even the bodies of the heifers were moved there, dragged along by the bulldog which provided our transportation. “We had to move them,” Lester explained to me in his high-pitched scratchy voice. “The other animals wouldn’t go near them. They were afraid of them. If we hadn’t moved them, the other livestock would’ve starved.”

Lester had brought along a medical kit they used on the animals. It was primitive, but did have a scalpel, gloves, and some tourniquets I could use, if necessary. When I inspected the first shriveled corpse, I could see that the tourniquets would not be necessary. There was not a drop of liquid left in the carcass.

According to Gadfeld, there had been no sign of illness from anyone who interacted with the corpses, but I still donned gloves and wore a bandana over my nose and mouth out of safety. I started with a shriveled body of a lamb which looked like a deflated children’s toy. I inspected the animal’s woolly coat which remained fluffy and coarse to the touch. There was a familiar chemical odor to the animal, but I couldn’t place it. The genitals were removed by a perfect cut, almost machine-like in its precision. I thought of my own scalpel and doubted I could make such a cut. I wasn’t sure I’d ever seen one so clean. I turned my attention to the mouth and eye sockets of the animal. The eyes were missing, but it didn’t seem like they were ripped out, more like they had never been there in the first place or had shriveled until they ceased to exist. The tongue was removed with the same pin-point cut as the genitals. I inspected the entire body and found no obvious puncture wound where the blood could be drained. I next made an incision into the animal’s carcass and began my autopsy. I removed the liver and stomach. I checked the spine and intestines. Despite being completely shriveled, I detected nothing wrong with them. I could not fathom who or why someone or something would do this to the sheep.

I found the same characteristics with the heifer and goat I inspected as well as McRory’s dog. They all had a shiny coat, all drained of liquid with genitals and tongue removed. All missing their eyes. None had any sign of a puncture wound.

After I had learned what I could from the corpses, I packed up the veterinary supplies and joined Lester at the bulldog. “Any ideas, Doctor?” young Lester asked as he sat up. He had taken advantage of his time as my escort to nap in the truck while I dd my surgical investigation.

“I can rule out any attack from an animal. No bear, cougar, or canine would have attacked in such an unusual manner. I believe I can also rule out ingestion of poisonous plants. I can’t fully rule out poisoning though. It may explain the smell about the animals.”

“They sure do stink,” Lester yawned. He had stepped out of the truck, cracked his back, and gave a stretch of his arms. “Still, I can’t imagine poison could cause their tongues to fall out.”

“Yes, that’s true,” I said. I rubbed my chin, thinking to the surgically removed genitals, trying to think if I’d missed anything. “And there were no tracks around the animals?”

“None whatsoever. It almost looks like they were killed by a giant mosquito. One that eats eyes, tongues, and unmentionables.” Lester looked at me funny for a minute, seeing my attention had drifted. “What’s on your mind?”

“Is the mark still clear in the wheat field?”

“Clear as daylight from the sky.”

“That’s good. I’d like to have a look at it myself. Would that be a problem?”

“Shouldn’t be, just depends on Mr. Alexander’s schedule. He’ll be finishing up in the fields about now. I’ll take you to him.”

*****

Emory Gadfeld eyed the gaunt figure of Solar Pons making sure he didn’t try anything funny with his father’s books. The detective had been amazed when he saw Gadfeld’s father’s collection. Pons stood gawking before the ancient volumes. He opened the glass door of the book case carefully and removed each book with a gentleness one does when carefully lifting a newborn babe.

The detective started with The Necronomicon, perusing the book’s fragile pages some of which had the ghastliest illustrations of otherworldly beings he had ever seen. Pons then looked over De Vermis Mysteriis and The Book of Azathoth. The detective’s hawkish nose stuck into each book, his eyes peered through the magnifying glass, studying not just the words but the paper and binding of each volume.

Gadfeld wanted to leave Pons alone in the library to take a break and run through his daily regimen. He didn’t want his body to fatigue while he was away from rowing, so he had developed a daily training, working his muscles through lifting various weights around the farm and running several laps around the family’s acreage. But Gadfeld couldn’t bring himself to leave Pons alone. He thought he was being careful, but the more he questioned himself, the more he realized that it wasn’t caution. The detective had proven himself trustworthy. Gadfeld needed to swallow his pride and admit his unease was not concern but jealousy. He was jealous that the detective understood his father’s weathered texts, could connect to them and therefore connect to his father in ways Emory never could. His older brother, the inheritor of the farm could, but Emory was left out of that equation. Like Alfred, the second born son to Victoria, he would always be a Prince and never a King. Gadfeld loathed himself for this admission, and instead of stewing to the point of rage, decided to talk with the detective about the texts. Perhaps he could connect with his father that way.

“Are the texts helpful?” Gadfeld asked quietly.

Pons lifted his beak from The Book of Azathoth. “Hmm?”

“Are the texts helpful?” Gadfeld repeated. He was a little perturbed for having to ask twice.

“Yes,” Pons answered and went back to examining the book.

He was starting to feel exasperated. Was this expert detective paying him the least bit of attention? Gadfeld then noticed a folded piece of paper sticking out of the middle of The Necronomicon. “What’s that paper?” he asked, pointing directly to the sheet jutting out of the ancient tome Gadfeld purposely angled his hand in such a way that Pons would have to notice.

“Ah,” the detective’s eyes widened, and he sat up at Gadfeld’s father’s desk. He tilted his head back so as to meet Gadfeld’s gaze. “That is a translation page, a key to help readers interpret the book. I believe your father created it for your brother.” Pons pulled the sheet from between The Necronomicon pages and handed it to Gadfeld.

“Yes,” Gadfeld confirmed, eyeing the manuscript. “This is Father’s handwriting.”

Pons politely nodded, gave a little smile, and turned back to his books. Gadfeld bristled thinking Pons was placating him. He sees me as an inconvenience, Gadfeld thought to himself. He could feel his shoulders tensing. He just wants me out of the room. I’m nothing more than a distraction to him. Gadfeld decided he would not give the detective what he wanted. Gadfeld was trying to think of a way of expressing his anger at Pons’s contempt towards him when the detective himself surprised Gadfeld by saying, “Would you mind helping me?”

“I’m sorry?” It was now Gadfeld’s time to need something repeated.

“There is a section of The Necronomicon which I believe could be helpful to the case,” Pons explained. He stood and took the book from the desk, carefully flipping to a section at the front of the tome. “Here,” Pons said, pointing his index finger straight between the pages. “This section has a brief history of creatures that lived on Earth before the time of man.”

“You mean the dinosaurs?” Gadfeld asked. He was puzzled as to how ancient history could impact the slaughter of his livestock.

“Same time period,” Pons explained, “vastly different creatures.”

“And this will help the case?” Gadfeld couldn’t fathom how it would.

“Yes, for I believe that the person or persons responsible for harming your animals is or are followers of The Great Old Ones, the Gods you shall learn about in this segment of the book. Take notes on their history, for it could explain what the perpetrator wants and what shall be his next move.”

Gadfeld sat in the sofa towards the back of the library and pulled the coffee table up so he could rest the book, notepaper, and pen there. If he was going to spend the afternoon completing translation work, he might as well get comfortable. He started translating the first few passages, “Long ago, before the time of man, when the thunderous lizards walked the Earth, a great and terrible war raged between two races from the sky....”

*****

It wasn’t until rather late in the evening when Pons and I were able to meet and discuss the intelligence I had gathered during the day and the research he had conducted in the Gadfeld library. We had seen each other briefly when I returned from my time with the field workers. Pons was at dinner. I had supped with the farmhands, and I was going to join Pons and Gadfeld at the table to speak with them, but through knowing looks, I could see that Pons didn’t want me to express anything but pleasantries. My detective friend supped a small amount of food before excusing himself and returning to his studies. It was close to ten that evening when I was laying on my bed and scribbling notes about the day in my journal. I was just getting to write my notes about O’Brien when I heard the turn of the door knob. I sat up as Pons swept into the room, a stack of notes clutched to his breast.

“I see you’ve been productive,” I said in greeting my friend.

He grunted in acknowledgement and replied, “As have you.”

I asked Pons to give me a minute to jot down some final recollections from the day before we spoke as I knew we had much to discuss. My friend spread out on the floor and started doing his stretching exercises he learned from his time spent in the orient.

After we had both completed our activities, we sat across from each other on our beds and began to report our activities for the day. Pons had me go first.

I told my friend of what I had observed with the animal corpses. He nodded when I explained that I did not believe there was a poison which caused the death and mutilation of the creatures, but I couldn’t fully rule it out.

“I concur with your reasoning, Parker. Even without laboratory tests, I believe we can rule out poisoning. Tell me of what you observed in the crops.”

“Lester brought me to see Mr. Alexander. Very friendly bloke. We struck it off well. It ends up that the crop duster he flies is an Airco DH.9, the same model he flew in the Somme. Anyway, he took me up and gave me a bird’s eye view of the field. The symbol that Gadfeld drew for us was accurate. I was surprised at just how big the marking was, though. It must have covered ten acres, maybe more. I’ve never been very good at estimating.”

“Did Alexander say if there was any evidence of who created the crop design?” Pons queried.

“I asked, but he said that unlike the animal corpses, this was an area where workers were present daily. There were plenty of footprints around the sign, but there was no way of knowing who was responsible based on prints.”

Pons closed his eyes, in thought for a moment. Then he quietly asked, “And did you speak with many of the workers?”

“Yes, I dined with them in the mess hall. There’s a great group of ten men, plus the twins. Most are Irish immigrants, some are locals. You can tell the difference from the ginger hair and the lengthy arms of the locals. The only one who stood out to me was O’Brien. He was a dark and brooding man with the blackness the Irish are well known for etched into his face. While the others spoke with me and invited me into their groups, he watched me as though I were a German invader.”

“Did you speak with him at all?”

“I tried to strike up a conversation with him, but he answered in short, curt responses. I told him how much I like Blue John thinking it would elicit a sharp positive or negative response. He glared at me and shrugged his shoulders a bit. I wasn’t sure how to read that response. I asked him if he had a good day, and he responded with a shrug of his shoulders and a curt, ‘yes.’ I then tried to get him to talk of his employment thinking that after a long day in the fields his tongue might loosen up a bit. I asked him how long he worked at the farm, and he said ‘ten years’ but then looked down at the table so as to disengage in conversation with me. I was going to ask a follow-up question asking if the farm had changed much in those ten years, but he got up from his seat and walked away, leaving his empty stew bowl behind.

“Another Irishman picked up the bowl soon after O’Brien left. ‘Don’t mind him,’ he told me. ‘He’s not much of a talker.’ The worker left before I could ask him any questions. I don’t know if O'Brien has anything to do with the shenanigans we are investigating, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he did. I asked some others about O’Brien, and they all spoke in favor of him. They said that’s just the way he is, a quiet type, but he is a good worker. I listened to them, but the whole time, I kept thinking of those cold eyes and how they stared at me.”

Pons considered this information. I paused so that he could ask me a question, but he motioned with his hand for me to continue my story. I then told Pons that after my dinner with the farmhands, I said my goodbyes, and Lester gave me a ride back to the farmhouse.

“When I got in, Mrs. Alexander informed me that you were still conducting research in the library. I thought of meeting you there but figured you wouldn’t want to be disturbed. I decided to take the opportunity to return to the room and jot down my notes from the day while I waited for you.”

I paused, expecting my friend to ask me clarifying questions about my day. He was looking intently at his hands, his fingers steepled before his eyes, focusing his mind’s eye. After what must have been a full minute, Pons lowered his hands and said, “Very good work.”

“Thank you, I did my best, but have I learned much that is useful?”

“You have,” Pons answered. “There are many pieces at play here.”

“I see,” I said, although I really didn’t. “And how did your research go?” I inquired.

Pons pulled his arms up behind his head, stretching out his back. “It went exceedingly well. I have learned so much in just a very short amount of time, barely scratching the surface of the knowledge contained in those texts.”

“Anything that can help us with this case?”

Pons talked as he removed his shoes and then sprawled out on his bed. “Yes, I learned all I need to know to solve this little problem.”

“But how?” I blurted. I couldn’t fathom how writings older than man could help with a modern-day case.

Pons let out one of his odd silent chuckles. “With help from Ronald Gadfeld.”

“Don't be ridiculous, Pons,” I practically shouted. “Ronald Gadfeld is dead.”

“That he is,” Pons said, sitting up with a mirthful expression upon his face. He was having a bit of fun with me. “But he left behind copious notes, particularly with his papers from a fragmented text called The Pnakotic Manuscripts.”

“And from these notes, you believe you know the cause of the animal deaths?”

Pons’s playful demeanor shifted all at once to a cold sobriety. “I do, Parker. God help us all, I do. We are fortunate. We have time to stop the killings from spreading. Tomorrow, I shall prepare, and then two days hence, we should be able to end it all.”

I wanted to ask Pons more, but I could tell his cryptic answers were all I would get that evening. It had been a long day of travel and work. We were both ready for slumber.

We dressed for bed, and before turning off the light I did ask Pons what Emory Gadfeld thought of all of this. “He is a smart lad, Parker, with a suspicious nature. He wouldn’t leave me alone in his father’s study, and so I put him to work.”

“He assisted you in your research?”

“A bit. I had him looking into the historical readings from The Necronomicon. I made sure he only read sections which could not get him into trouble.”

I wondered how any sections of a book could get anyone into trouble.

Pons continued. “He thanked me for letting him partake in the work. I believe it made him feel closer to his father.”

I was going to ask Pons more, but his heavy breathing told me he was already asleep.

*****

Gadfeld found himself wandering in a great cyclopean city lit by a gibbous moon in the sky above. The buildings on either side of him were made of giant stone slabs, so tall were they, that even arching his back, Gadfeld couldn’t see the top of the structures. The air was fetid probably from the thin lair of green slime which covered all the buildings surrounding him. Even the damp dirt path below his feet was speckled with odd growths in strange putrid hues. Where am I? Gadfeld asked himself. How did I get here? Gadfeld’s brain tried to fathom the odd angles of the structures surrounding him, some of which seemed to do the impossible, appearing both square and round.

At one point, Gadfeld came across a skyscraper with the symbol that was arched in Gadfeld’s fields cut into the wall above the building’s entryway. Gadfeld found himself inside this strange building in a cavernous room with a cathedral ceiling. Lining the walls were small concrete pouches, each containing a slate like one would use in school. Gadfeld lifted one of the slates from its pouch and found that the tablet was not a structure to write on. Its face contained a grotesque image of a strange tentacle much like a squid, but one that can crawl upon the land. Gadfeld was horrified to see the image on the slate start to shimmer and move as if a segment of history was captured on the slate much as travelers on safari capture wildlife on film. There were hundreds of bulbous octopods, all shambling, pulling their slimy forms across the streets of the cyclopean city. Gadfeld shuddered and returned the plate to its sheath.

The young traveler pulled another slate from its resting spot on the wall. This one depicted an image so repulsive that Gadfeld believed he would surely go mad as his brain tried to process it. This monstrosity was nearly impossible to fathom. It was a bloated tubular creature, with five antennae like stalks emerging from the top of its head. Each stalk had an eye at its end, much like snails and other disgusting mollusks which crawl upon their bellies. These nameless beasts had five tentacle appendages which acted as legs and feet. There were also five mouths on its body, and even five bat-like wings. This creature resembled the lowliest savage beast, and yet Gadfeld could see that these monstrosities had an intelligence far above anyone born as man.

These... things... for that is the only word Gadfeld could use to describe them, appeared to be part animal with their eyes and mouths, yet also part plant or vegetable with their tubular bodies. The tablet showed these odd pentagonal creatures warring with the octopods. Both beasts used torches which emitted beams of light that were deadly to the other creatures. The war was savage with tentacles being lopped off and burning winged pentagonal things falling to the ground. The air was acrid and the sky itself seemed scarred from the brutal onslaught. One of the octopodal beasts made a guttural shrieking noise as the image of its burning body bubbled up through the slate. The beast flung itself backwards, its melting form getting closer and closer to Gadfeld until...

Emory jumped up from his bed and clutched his chest. He was coated in sweat, his heart thumping loudly in his ribcage. It was a dream, just a dream. Gadfeld looked down at his nightstand at the foul book which lay atop of it. The Necronomicon. Surely, his dream had come from his work translating that book. Gadfeld thought of the lean and lanky detective who had worked beside him and wondered if his dreams had been as horrifying as Gadfeld’s own.

There was light entering his room through the curtains, and Emory cursed for he knew that meant he had overslept. Yet, he felt like he hadn’t slept at all. Were you able to rest easy, Mr. Pons? Gadfeld asked in his mind. He wondered, Did the detective visit the cyclopean city of his dreams? Did his father? Gadfeld hugged his body tightly and teetered as images of the pentagonal winged beasts flickered in his mind. He may have stayed there for an hour or more fighting back the horrid images from his dream if he were not startled by a loud hammering upon his door.

*****

Pons and I woke early, feeling refreshed after the previous long day of work and travel. We made our way to the dining room where Mrs. Alexander supplied us with hot coffee and warmed rolls. Pons and I breakfasted, complimented the cook, and discussed our plan for the day. I inquired if I would spend the morning visiting the rented farms on Gadfeld’s property. I assumed Pons would continue his study of Ronald Gadfeld’s books.

“No, Parker, I believe that won’t be necessary.”

“But shouldn’t we be thorough in our investigation?”

“Thorough, yes,” Pons concurred, “but we shouldn’t waste time. We shall make a visit this morning which I believe will make the rest of our inquiries moot.”

My eyes widened and I was taken aback by this declaration. “And who shall we visit that will clear this matter up?”

“O’Brien!” Pons and I turned to see Mr. Alexander in the doorway looking furious. “I caught that fool in Mr. Gadfeld’s library, his face down in one of those godforsaken books. Emory’s sure to fire him now!”

“Hush now,” chastised Mrs. Alexander. She squeezed the locket she kept around her neck, and she gave a stern look towards Pons and me. “You two best not to report what you’ve heard here. And you,” she said, turning to her husband, “you be more careful!” The caretaker then lowered her voice and asked, “He’s still asleep on the desk?”

Mr. Alexander gave a nod.

“Emory’s still asleep. You and I can move O'Brien and he’ll never know.”

“I’m afraid that won’t do, Mrs. Alexander,” Pons said sternly. He stood from the table and gave a fierce glare at the married couple. “I was hired by Mr. Gadfeld to look into matters here, and I will not withhold any information from my client.”

Mrs. Alexander bristled and turned on her husband. “See what your big mouth has led to.”

Her husband then turned on her. “Why do you always have to blame me for other people’s mistakes? That fool did it to himself.”

“Well, if you ask me,” she rebutted, “you didn’t help the poor man. He’s been so shook up since Mr. Gadfeld’s passing. Poor man’s always off on his own.”

“That will be enough,” Pons snapped at the bickering couple. “Mr. Alexander, go wake Mr. Gadfeld and explain to him what has happened. Do not have him go to the library for as far as I am concerned that is now a crime scene. Parker and I must sift through the evidence.”

Pons and I found O’Brien slumped across Ronald Gadfeld’s desk, snoring loudly. Acting as a pillow beneath his head was one of the old texts, though I couldn’t tell which one as the book was open, hiding the title on the spine. Sticking out from beneath the book were several handwritten pages. Pons smelled O’Brien’s breath and gently checked his pockets where he found an empty whiskey flask.

“He’s had a lot to drink, Parker. When we wake him, he will have a pounding headache.”

I nodded in agreement for what Pons said would be quite obvious to anyone with or without a medical background.

Pons then carefully removed the papers from below the ancient tome on the desktop.

“Did he write that?” I asked wondering why O’Brien would spend his time deciphering an ancient text.

Pons shook his head, no. “This is Ronald Gadfeld’s handwriting.”

“What’s it say?” I asked.

“It is a translation from De Vermis Mysteriis,” Pons motioned to the book under O’Brien’s head. “It is a summoning ritual for a deity known as Mother Hydra.”

“The Lernean hydra?” I asked. “The one that Hercules killed?”

“No, this being is much older, though I’m sure the Greek myth was inspired by this creature.”

“Why would O’Brien want...” Then, I caught myself. I thought back to the mutilated animals, their carcasses severed in what could only be a ritualistic fashion. “He did it!”

Pons looked at me, a wry grin on his face. He nodded his head, inviting me to continue.

“O’Brien had access to these books,” I explained. “Somehow, he started worshipping this creature. The animal mutilations and the symbol in the crops were his way of worshipping the monster.”

“Well done, Parker,” Pons gave a little clap of his hand. “You’ve drawn all of the conclusions that they want you to draw.”

My face dropped at Pons’s proclamation, but before I could ask him to explain himself, we were interrupted for the second time that morning. The door to the library flung open and in stormed Emory Gadfeld, followed by a complaining Mr. Alexander asking him to stop.

*****

Gadfeld charged into his father’s study like a bull pursuing a matador. He felt nothing short of pure hatred towards the man sleeping in his father’s study, the man who had caused him so much pain these last few weeks, the man who had kept him returning to his normal student life, the man who had kept him in Blue John, kept him in torment as he dealt with mutilated animals and otherworldly beings which haunted his nightmares.

“Get up!” Gadfeld yelled. He pulled O’Brien up by his hair and flung his head back. O’Brien, whose eyes were even more bloodshot than Gadfeld’s let out a yelp. He rocked back in the desk chair and almost tipped over. The man looked about rapidly, like a fox surrounded by bloodhounds, not sure what to make of his location and everyone around him. When he saw the fury in his employer’s eyes, he cowered and put his hands above his head to fend off any additional blows.

“What do you have to say for yourself?” Gadfeld snarled. O’Brien looked to each person in the room, his eyes pleading, much like a child caught with his hand in the cupboard, looking for mercy instead of receiving a thrashing.

“I don’t know,” O’Brien stammered. “What am I doing here?”

“Stealing from Father’s collection, but you got caught, you drunk! You were too stupid and fell asleep during your robbery.”

“No!” O’Brien shook his head. “No.” Like he did when I spoke with him the night before, O’Brien lowered his eyes, looked back down at the desk, and said, “I didn’t.”

Gadfeld was about to rage at the man again, but Alexander stopped him. “Let the man speak, Emory. He says he doesn’t know how he got here.”

“A likely story,” Gadfeld spat. “And one he can explain to the police!”

O’Brien put his face in his hands and began to weep.

“Mister Gadfeld,” Pons called to the man firmly. “A word, please.”

Emory had his fists clenched and looked with absolute disgust towards his blubbering farmhand. If Pons hadn’t spoken, he surely would have pummeled the man. But Emory was able to harness his rage and followed Pons out into the hallway.

“What is it, Pons?” he asked the detective curtly.

“I would not be so... intimidating... towards Mr. O’Brien.”

“Not be so – damn it, man. He was caught red handed.”

“Be that as it may, we do not know why, exactly, he was in your father’s study, and we are not the ones qualified to be questioning him.”

“Not qualified?!? I’m the man’s employer.”

“But you are not an agent of the law.”

“I see, so you do think the police should be called in on this matter.”

“As soon as possible,” Pons explained. “Once O’Brien is arrested and taken into custody, the police will be able to find out why he was in your father’s study and what he had to do with the slaughter of your livestock.”

“He’ll pay for that!” Gadfeld gritted his teeth and clutched his hands together as if he were throttling a ghost.

“I’m sure he will. For now, I’d recommend calling your local constable.”

*****

After Gadfeld went to summon the police, Pons and Alexander escorted O’Brien to a room in the basement. Pons and I stood guard while we waited for the constable to arrive. My detective friend did ask O’Brien a few questions, but the man was too shaken to give much more than simple answers.

“Sprichst du Deutsch?” asked Pons. Then, “Mutter Hydra wird für uns alle kommen.”

O’Brien stared at the wall. Pons repeated, and the man said, “I don’t understand.”

Once Constable Corbyn arrived and took O’Brien away in irons, we had already reached mid-day. Gadfeld thanked Pons and me for our time, and Pons surprised me by asking his client if he could give us a ride to the train station, so we could catch the 3:15.

“Of course, Mr. Pons. It’s the least I can do after having you come all the way from London only to have the fiend blunder his way into being caught in the act.”

“No problem at all,” Pons assured Gadfeld. “Parker and I love seeing the countryside. Isn’t that right Parker?” Pons called to me.

I politely agreed with my friend even though I really didn’t like long train rides, particularly when all they did was waste my time.

Pons was rather quiet when we packed our bags. I asked him questions for I could tell that my friend was withholding information from me. He merely replied “All in good time my friend. All in good time.”

At two that afternoon, Gadfeld had Pete and Lester load our bags in the trunk of the car. We said our goodbyes to the lads and to the Alexanders.

“Come back and visit again,” Mrs. Alexander said warmly.

“You’re always welcome.” Mr. Alexander assured us. I asked Mr. Alexander to be sure to give my regards to the field hands.

Soon after, we were in Gadfeld’s jalopy, driving along at a leisurely pace towards the train station. “Will you be returning to university soon?” I asked Gadfeld.

“Yes, doctor, as soon as I can. We’d been holding off on harvesting the wheat. Now that the crime’s been solved, that will be the main work for the next few days. When everything appears to be in order, I’ll return to Oxford. Most likely arriving by the end of next week.”

We had driven past a few farms when Pons told Gadfeld to make a stop along the way. “Where to, Mr. Pons?”

“To see Mr. Hutchcroft.”

Gadfeld swerved when Pons made this request. Fortunately, there was no oncoming traffic. Our driver balked. “The Hutchcrofts!”

“Yes. It is of the utmost importance that I speak with Mr. Hutchcroft.”

“May I ask why?”

“It concerns the books in your father’s library and why he wanted to purchase them.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Get us to the Hutchcroft House, and you shall my lad. You shall.”

We soon pulled into a rugged gravel road, followed it past several workers tending to crop, and arrived at a small stone castle on a hill overlooking the fields. I imagined that this must be the original home of the lord who oversaw the farms of Blue John.

Gadfeld parked the car in front of the house. No one was out front, and I figured that all the workers were out in the fields or tending to the animals. Pons stepped from the car and beckoned for us to follow him to the front door. Gadfeld let out a resigned sigh, probably thinking to his beau and what would happen if Mr. Hutchcroft found out about their feelings for one another. He walked stiltedly, taking his time. I wasn’t sure if Gadfeld would change his mind, run back, jump in the car, and hightail it out of there; however, he did join the detective and me on the front porch. Pons rapped loudly on the door and several chickens who were roosting on the front stoop clucked in response.

We waited a few moments, and Gadfeld suggested that perhaps everyone was out working, completing chores, or away running errands. Pons was about to knock again when we heard the bolt of the door slide back, and then the door opened a crack. I saw a dark eye peer out from a lined face. “What do you want, Master Gadfeld?”

“Sorry to bother you, Mr. Hutchcroft,” Gadfeld stammered. “It concerns my father.”

The door opened further at this proclamation. Hutchcroft stepped out onto the porch. He was a tall and spindly man with leathery skin, and a twisted unkempt beard. He gave me a once over and then did the same to Pons. My detective friend started fidgeting with his necktie. I noted they were the same motions Pons made when Gadfeld first visited us in Praed Street.

Hutchcroft’s suspicious look turned to one of surprise and then delight. His lips turned into a toothy grin which split open to reveal yellowed teeth with gaps between them. “Heh- heh-heh,” Hutchcroft cackled. He made a similar motion with his hands in response to Pons. “Your eyes are open,” he said to Pons. Then he looked to Hutchcroft, his face beaming with delight. “Your eyes are finally opened as well, my boy. You’ve managed to learn what I always wanted your father to teach you. Please come in. I’m sure we have much to discuss.”

“Sarah,” the old man called out when we followed him into his home. The house was well decorated with checkered curtains and a floral wall paper pattern.

“Yes Papa,” came a melodious voice from down the hall. We then heard approaching footsteps and soon Sarah Hutchcroft stood before us in all of her radiance. She was surprised to see Gadfeld in her house and blushed slightly when their eyes met.

“Please put the kettle on for our guests. They shall be here for a while.”

*****

Gadfeld had always taken pride in his logical reasoning, not following some of the superstitious beliefs of the locals, that when cows lay down in fields it meant a storm was brewing even if there wasn’t a cloud on the horizon. Now, from what Pons and Hutchcroft explained to him, he was in a whole new world, one of monstrous creatures with a great indifference to the plight of man. Oddly, it was his basis in logic and the research he had recently completed in The Necronomicon, which allowed him to accept the information that had been presented. He had been greeted warmly by Mr. Hutchcroft, and he finally learned the origin of the feud between the two families.